“There is a very primal side to me. I suspect we all have this, but are so afraid of it that we prefer to deny its existence. This denial is more dangerous than acceptance because the “killer,” that mad primitive chimpanzee part of us, is then not under ego control. It’s why a good Baptist can get caught up in a lynching. It’s why a peace advocate can kill a policeman with a car bomb.”

What It Is Like To Go To War, Karl Marlantes, pg. 30

The War

Last April, a long conversation in Hein Dining Hall birthed an idea a year in the making. Heart & the Fist is an original one-act play co-written by and co-starring Ella Mae McCarthy and myself. Our joint Capstone effort as Dramatic Media majors that we are also co-directing alongside fellow Senior, Aliyah Harris.

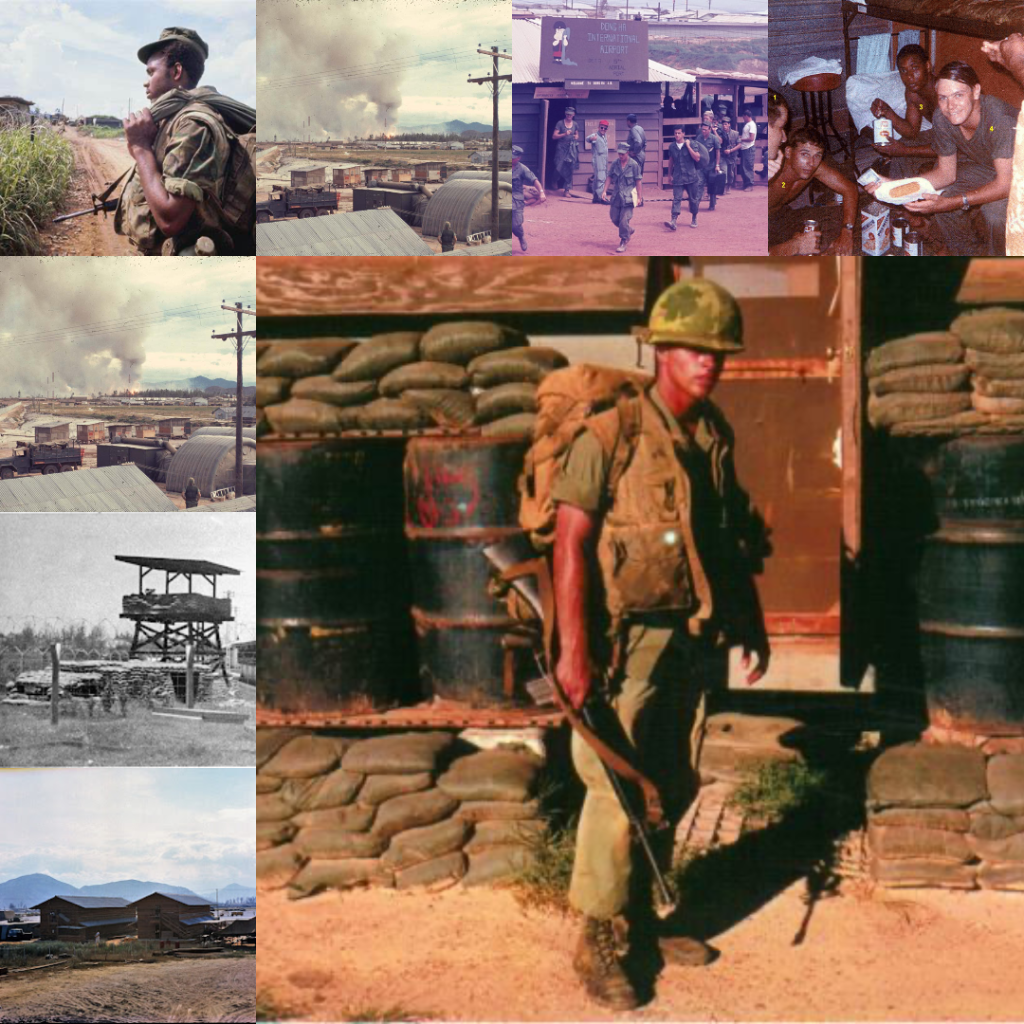

The story is set in 1970, amidst the height of the Vietnam War. Young couple, Cash & Mary, are staunch anti-war activists, leading their Student Democratic Society. However, when Cash receives his draft notice… their world is upended.

In the role of Cash, I have had the opportunity to do more research and analysis than I’ve ever done for a role before. Since April 2024, I have immersed myself in the world that is the Vietnam War. Time and time again in that research, the question soldiers often have to confront is—why?

Why would men voluntarily go through war, and what does “voluntarily” even mean? In circumstances, like the draft, where conscription is enforced by the law, how much free will is really in the hands of the individual? Should that choice be made on loyalty to his country or loyalty to his loved ones? These are ideas we get to explore deeply within the play itself.

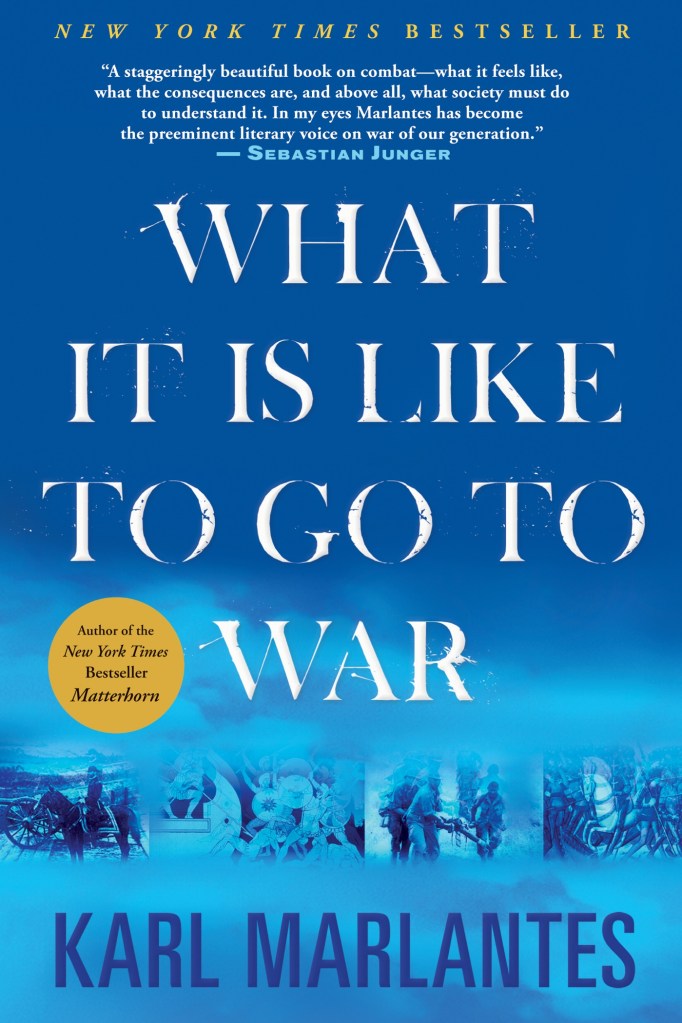

In Karl Marlantes’ book, What It Is Like To Go To War, the former Marine draws from his experience in Vietnam to take an introspective look into the psychology of war. He aimed to inform future soldiers and the civilian world of what is really asked of those in combat, both physically and emotionally. Marlantes seeks to answer the “why” as well.

“The hard truth is that ever since I can remember I have loved thinking about war… There is a deep savage, joy and destruction, a joy beyond ego enhancement. Maybe it is loss of ego. I’m told it’s the same for religious ecstasy. It’s the child toppling the tower of blocks he’s spent so much time carefully constructing. It’s the lighting of the huge bonfire, the demolition of a building, the shattering of a clay pigeon. It’s fire crackers and destruction derbies on the Fourth of July. Part of us loves to destroy.”

~What It Is Like To Go To War, Karl Marlantes, pg. 63

Another way of looking at the euphoria of combat is as a source of gender affirmation. Now, we don’t typically think of war in such terms. However, there is an extremely common idea of the military “making a man out of you.” This image of the honorable man who will sacrifice himself for the greater good hangs in every boys’ mind, soldier or not. He might grow up admiring and seeking a sense of duty like his heroes before him. Athletics regularly fill this “rite of passage,” providing a simulated war-like experience where men seek to dominate their enemy.

This is evident when soccer and rugby teams of New Zealand origin perform the Haka—a Māori tradition—before the opposing team. There is the Ha’akoa—which translates to “dance of the warrior”—performed by the University of Hawaii Football team as apart of their pre-game rituals. These displays of cultural pride and unity feed into the warlike atmosphere.

You could ask the high-school football player who isn’t trying to make it to the NFL, or the weekend boxer who fights at his local gym. Why would they take part in a knowingly dangerous, violent event where they make no tangible benefit? I see this pursuit as one of purpose, a motivation to gain and maintain the status of a “real man.” A status with a lack of usefulness in daily life.

This is not to discredit the women who do serve in combat and compete athletically for love of the game, but rather an insight as to why these constructs are so strongly tied to masculinity in the first place. The man who craves but cannot live up to this standard of manhood that he idolizes, may struggle to find value in the other qualities of himself. I myself have to often fight the urge to sound “cool” and look “manly” on stage, and let myself embrace the perceived “weaker” emotions.

The Process

In the Vietnam era, a Marine in Basic Training would be expected to undergo a strict eight-week program consisting of:

- Physical Conditioning

- Rifle Marksmanship

- Military History & Customs

- Team Building Exercises

- Sanitation & Hygiene

This is all accompanied by the intense scrutiny and commentary of the drill instructor, all while having a 5 a.m. wake up time. Once in Vietnam, soldiers out on active mission would be expected to carry at least 80lbs worth of gear with them.

As of this article’s release, I am currently in the final week of a pseudo boot camp of my own. This has involved waking up at 5 a.m. Monday through Friday and building my way up to running 2 miles every day, with a 12-pound weighted vest. In addition to this, has been heavy strength training and plyometrics 3 days out of the week. All being followed by an hour of some form of Vietnam War History. I was not allowed to use this time to work on separate assignments or projects. The hardest part by far about this experiment was waking up at 5 a.m. every day.

Note: JaCori is an extreme night-owl by nature and a procrastinator by habit.

The second hardest part was the monotony. If I did not take the liberty of starting to mix up my running path, I can almost guarantee you I would not have completed this boot camp. The physical aspect of the training has probably been the easiest side to it. The real test comes in waking up tired the next day to do it all again.

And again.

And again.

And again…

The biggest discovery I could share is how glad I am not to be doing this anymore. Genuinely, I do feel a great sense of accomplishment over something I didn’t think I would be able to do. One could argue in doing this, I am seeking the same sense of purpose and “rite of passage.”

It was always a priority that I take this project seriously because of the real lives transformed and changed by war. What I understand the most, after all my research and character study over the past year, is that I don’t understand.

We have the privilege of playing dress-up, philosophizing the actions of those involved, and doing this work for fun. The discomfort I put myself through temporarily and safely at home is but a small resemblance of the reality. We can only try our best to mirror the soldiers and loved ones affected.

My respect goes out to all men and women of the U.S. Military, past and present.

Heart & the Fist will premiere in the Weston Studio Theatre

Apr. 24th 7:30 p.m.

Apr. 25th 7:30 p.m.

Apr. 26th 2:30 p.m/7:30 p.m.

(talkback with Cast & Crew to immediately follow closing performance)

- Old Dog New Tricks- Men’s BasketballTLU student media presents Monica Sitachitta learning how to play basketball with Texas Lutheran Basketball players: Mason Wallace, Teddy Tapken, Semaj Edwards.

- A Semester Away: Expect the Unexpected!Inspired by a recent conversation with my roommate, I’ve been reflecting on how my study abroad experience has differed so greatly from the one I’d… Read more: A Semester Away: Expect the Unexpected!

- Day in the Life of Xi Tau’s President Serina IbarraLet me introduce you to Serina Ibarra. A student here at Texas Lutheran University, who never imagined joining a sorority yet is here leading one.… Read more: Day in the Life of Xi Tau’s President Serina Ibarra

- Old Dog New Tricks Episode: VolleyballOld Dog New Tricks Episode: Volleyball